Category Archive: Uncategorised

Waterbirds in the landscape Week 5: Gulls

October 2, 2023

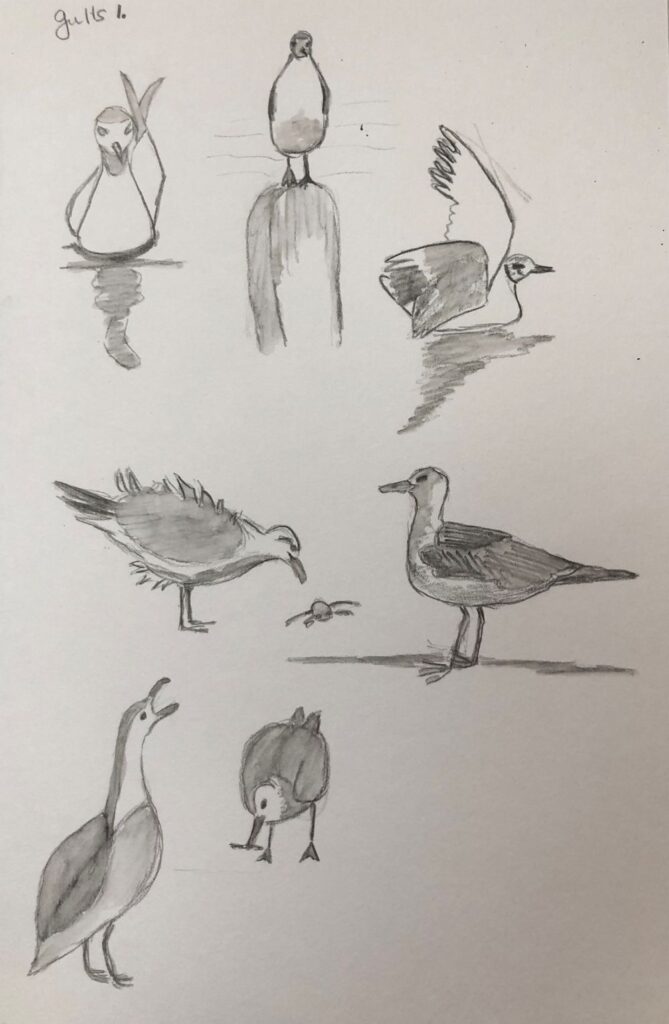

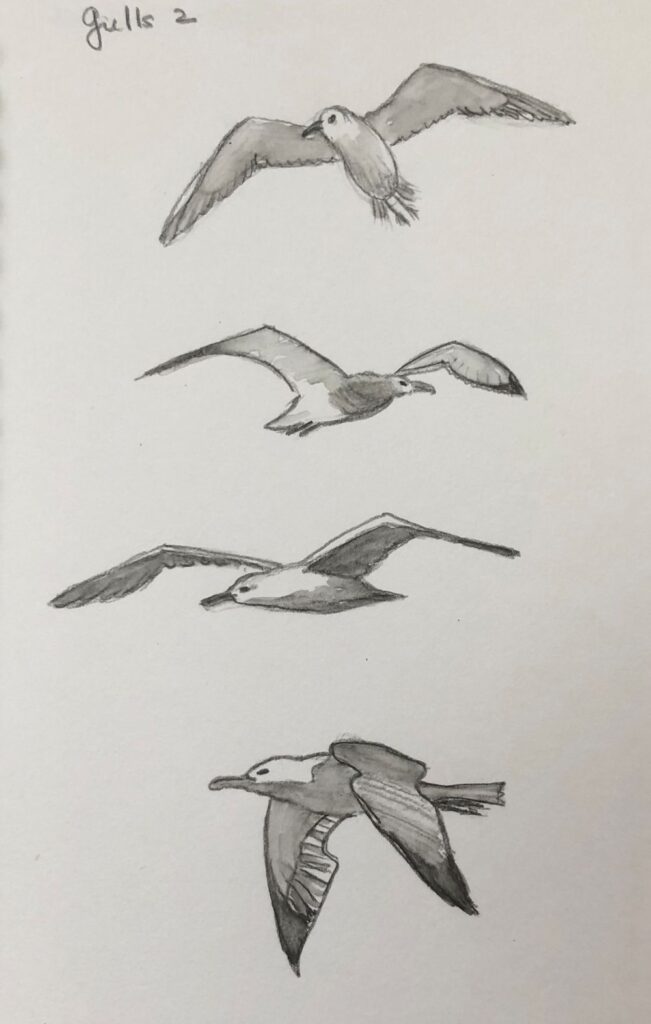

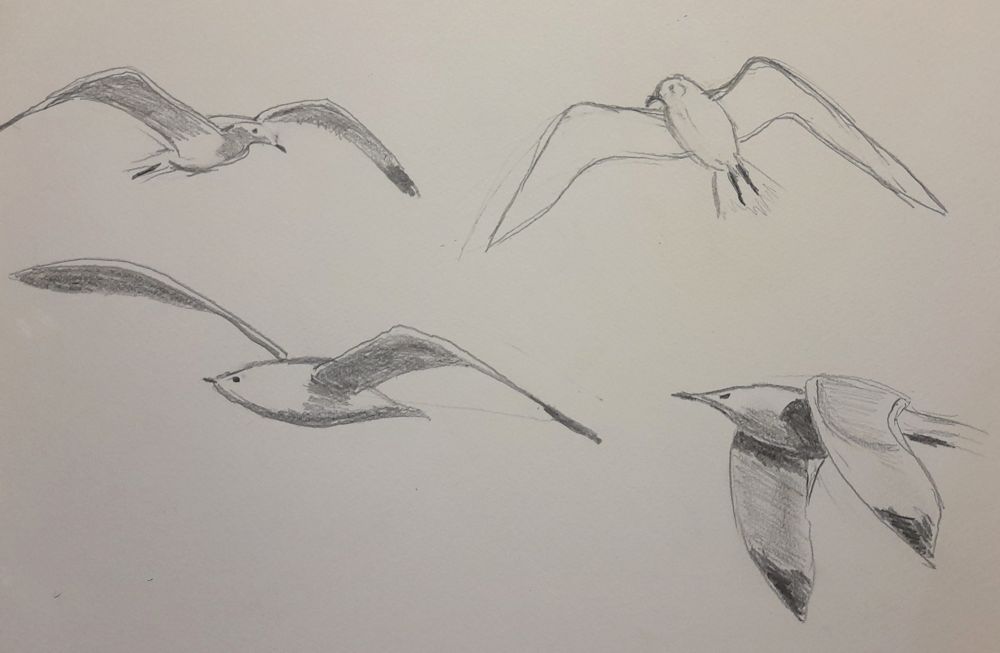

This week we’ll be looking at gulls, on the coast and further inland. Gulls spend a lot of time in the air and during the session we’ll be sketching birds in flight, on the water, and standing, before planning a painting. The herring gull above is probably one of the most familiar. It’s neck is quite stocky, head and front are pale/white, wings a slate grey with black and white wing tips and its legs are pink.

You may like to start drawing with the head, but another way is to look at the body shape as it appears from the angle the bird is being viewed. From the side the body and wings when folded form an almond shape, flatter along its back and with an added point for the wing tips. The thick neck and head shape scan then be worked on, the beak added and then the legs positioned. To ensure the bird is well positioned with relation to what it is standing on, it’s a good idea to draw this in early on and then draft the main shapes tentatively at first so that adjustments can be easily made before adding more definite marks. As you become more accustomed to the shapes, accurate observation will allow more confident and accurate lines to be made earlier on in the work.

Remember to look at the overall length and breadth of the bird and where it is to be placed on the page. If much of the landscape is included think about the scale of the bird in relation to its surroundings.

You may like to consider a painting with more than one bird and/or different kinds of bird.

The photos below were taken in Kensington Gardens where there were herring gulls, great black backed gulls and black-headed gulls; some of which looked distinctly brown headed!

As in previous weeks think about the composition of your painting.

The image above gives a good clue to next week’s session when we’ll be looking at Coots and Moorhens.

Your Drawings and Paintings:

Waterbirds in the Landscape Week 4: Swans

September 24, 2023

Photos in this post are taken by me or my younger son and we are happy for you to sketch from them.

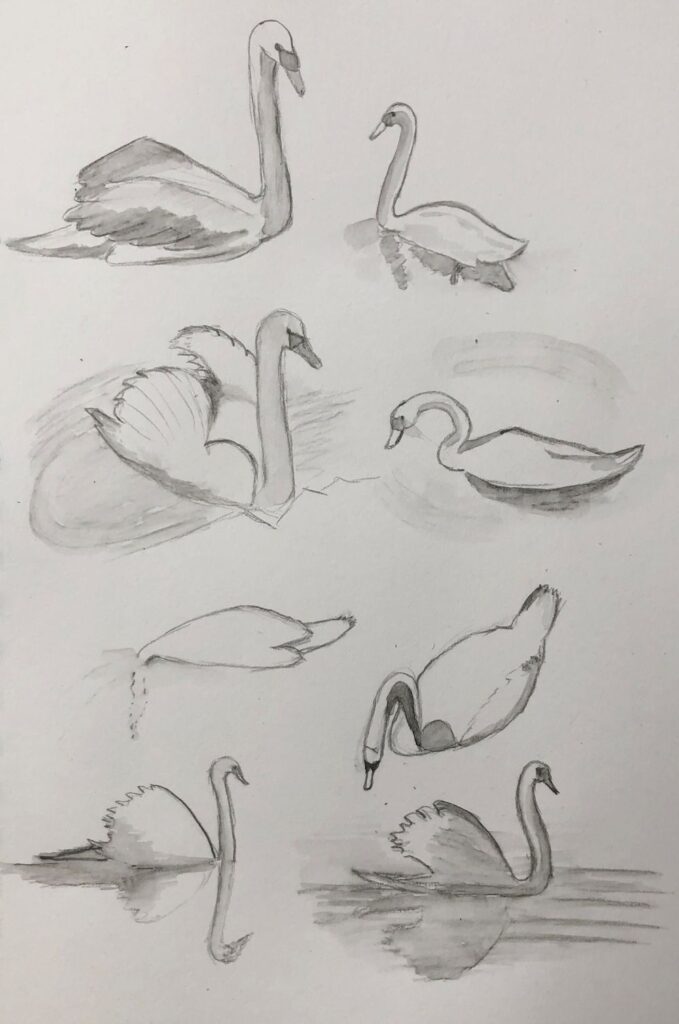

This week we are looking at the Mute Swan. It is the one you will all be familiar with and is easily distinguished from Bewick’s and Whooper swans by its orange beak and the bump above its beak. The other two swans are mainly winter visitors and have black beaks with a yellow patch. They also hold their necks more stiffly upright than the mute swan.

We’ll start by looking at the general form of the swan, mainly in the water, but I would also like you to consider the surrounding landscape paying particular attention to how much of the wider stretch of water and riverbank you would like to include in your painting.

Unlike the geese and ducks swans often swim with their wings slightly elevated as in the photo above but as you will see from photos later in the post they are just as happy to have them closely folded. Take some time to look at the grey-scale image above. The body is lying fairly flat in the water. Its tail feathers when down come to a graceful point and it is easy to see the form of the wings and their relation to the body and neck. Look at the angle of the neck and how it curves to join the body. Also look at the angle the head makes with the neck. If you are working from a photograph it is easy to measure to check overall widths and height and perhaps make a note of what proportions a rectangle just enclosing the whole bird makes. This will help you check its overall shape. Drawing the rectangle will also help you check the angles of the swan’s form in whatever “pose” it is taking up. The swan has 25 vertebrae in its neck whereas all mammals have only seven so it is no wonder the swan has such a mobile neck.

The photos immediately above and below show a swan taking flight from the water. The riverbank and the river and reflections give the bird its context. There is also the excitement of the disturbed water and reflections. If working in watercolour you will have to decide on whether to mask the swan, or paint around its pale form, or to use white gouache. You will also have to decide on how to represent the splashes of water; with spattering (white gouache or masking fluid or whether to scrape out with the tip of a craft knife as a final touch. If you are using pastel on toned paper you may be able to draw all with pastel but it is fine to add any small white highlights with gouache. Alternatively you may like to work in acrylic or a mixed media approach. Whatever media are used remember to experiment a little first on a separate piece of paper.

The two images below are the same photo’ cropped differently; the first gives a much better idea of the wider expanse of water and of the trees reflected in the water. Look at the tonal shift in the water as well as the high contrast of the swans against the water

If you don’t like the harsh line at water’s edge you may consider painting vegetation there instead or continuing with water. The photograph does not have to be followed completely; it is only a starting point. Within that do try to make the birds appear convincing though.

In the images above and below, elements other than the swan are important to the composition. Above we see the boat beyond the swan and also the swan moving through the reflection of the boat. There is a colourful interplay of shapes including the swan’s reflection and that of various parts of the boat.

In the more closely cropped image below, the swan takes centre stage but is still moving through an interesting pattern of tone and colour, in water only disturbed by the movement of the swan. Whether the branches hanging down from the top of the photo should be included is a decision for the artist but it would be a good idea to alter the position of the branch that cuts across the back of the swan’s head and follows the line of its beak. Always look out for objects causing similar difficulties in reference photos.

I was interested to see this rather disorderly brood of cygnets swimming ashore. Observe how the swan’s reflection is broken by the ripples in the photo above and how much more of the swan’s form is reflected in the calmer water of the image below.

Lastly, two images from a still water lagoon on the Great Ouse; I was intrigued by the shapes made by the swans and their reflections.

During the session we will make rapid sketches from some of these photos as a prelude to working up a more considered composition including more of the landscape/surrounding water. Hope you have enjoyed looking at these photos and looking forward to seeing work inspired by these photos, or your own reference, or better still from your own sketches made from the riverbank.

Your Paintings:

Waterbirds in the Landscape Week 3: Geese

September 14, 2023

Geese are like ducks with longer necks and can be seen as often out of the water as in it. This post includes photos of the Greylag Goose and the Canada Goose we are all familiar with. Take some time just to look at the various “poses”.

Body shape of the goose above is very much like a duck. Come to grips with this before adding the neck, head and leg as it paddles through the water. The Greylag Goose has a heavy orange beak, mottled mid and dark grey plumage on its neck, paler grey on its upper body and white below.

Below are photos of a Greylag landing, using its feet like water skis. Below the second photo is a version that has been flipped horizontally so you can practice drawing a landing from a different direction. Note the shadow areas under the wing as well as their shape and include the reflection as well as the splash!

Photo below is of a Canada Goose standing with its neck and head pulled back against its body. Note the position of the legs, about halfway down the body so it appears perfectly balanced. If seen directly from the front the neck would be directly above both legs. If the goose was moving forward the neck would tend to be directly above the leg that was doing most of the load bearing and would shift from side to side as the goose moves forward. This together with the plump appearance of the well feathered body creates the familiar waddling gait of geese and ducks.

A long flexible neck is a great aid to preening.

Note the shape from the rear and the well balanced form, and also the rather round dark eye.

We’ll make some rapid sketches during the session using a slide show of the photos above. If you have several photos of a particular goose in several different positions feel free to use your own; after all that is a bird you will have already observed. The choose one image and make a more considered bird portrait or composition of a goose in a landscape setting taking special note of movement of the water, reflections and of balance where the bird is standing.

Your drawings and paintings:

Waterbirds in the Landscape Week 2: Ducks

September 7, 2023

Having looked at the heron last week standing upright on the river bank, with its long neck and head turned toward the water intently looking for prey, this week our attention turns to the ducks who more often than not are found with their body mass in a much more horizontal position. That is till they amuse us by upending and diving for a tasty morsel of weed or start waddling around on the bank.

The UK is home to many kinds of duck from the teal and eider to the exotic mandarin. They share several common features including a broad flat keel and short neck and legs.

Take note of the body shape; in the water you can see its broad flat keel if its front is facing you when diving. Its neck is short and so are the legs with their webbed feet. Try drawing the duck itself in several different “poses” then look out for what happens to the water as it swims. Perhaps this week you could make a drawing or painting that includes the reflection of the duck in the water and how the water moves around it.

You may even find a situation where the ducks seem to be playfully swimming around while in the background, an ever-watchful heron is poised ready to fish.

During the session we’ll make some rapid duck and water sketches and discuss and start a composition where ducks feature either close up or animating the landscape.

Your paintings:

Waterbirds in the landscape: Week 1 Herons and Egrets

August 31, 2023

I sketched the arrival of the first few white egrets on a salt-marsh in New England and later painted this small watercolour evoking the birds, and the colours of the early autumn landscape.

Standing on a river bank watching birds, wondering at their movement and the patterns of water when a swan takes flight or a duck simply swims by, is exactly what we’ll be considering over the next few weeks.

We are starting with the heron and the related group of birds, the egrets. I chose the heron because of all the birds of the river bank, it is the heron that stays still the longest while watching for a tasty meal of fish so offers one less challenge when sketching from life. The heron will even shade the water arching his wings over like a living parasol so that the reflective surface of the water does not interfere with fishing!

Here are a few photos of herons and their relatives the egrets. Do some fast sketches preferably from life or from these or your own reference before launching into a more considered drawing or painting. These sketches should show the bird in various positions and flying if you can.

Before starting to draw look at;

The main body shape

Length of legs, neck head and bill in relation to the body

The angles made by legs neck and head in relation to the body

How the heron and the egrets hold and move their long necks

How the wings are folded over the body

Head and neck; the heron flies with its neck curved back into its body but egrets like swans and geese fly with their necks stretched forward in the direction of travel.

Observe how when the heron is about to skewer a fish its head moves forward and its whole body tenses ready to dive in. You can almost feel the anticipation of the hungry heron.

Colour

Composition

When considering how to paint a more finished work, decide exactly what you want to “say” about the subject, and then which references to use to show how the bird relates to the landscape. Also decide whether your painting is more like a portrait in a landscape setting; in the way that Gainsborough’s painting of Mr. and Mrs. Andrews is a portrait of the couple in their country estate setting, requiring a lot of detail, or whether it is the landscape that is of prime importance even if a flying heron in the distance forms the focal point. I have seen egrets in numbers together but herons tend to be solitary so this is an aspect that you could build into the feeling of your painting.

Looking forward to seeing the results and exploring the subject further on Wednesday.

Your paintings;

Portrait Drawing Week 6: Putting it all Together and Hair

July 19, 2023

This week we’ll put it all together with an accent on hair. Just as vegetation clothes the underlying topology of the landscape, hair clothes the head, so it’s important not to lose track of the underlying structures of the head. In the portrait above the hair was depicted largely as masses of tone with linear marks showing the direction in which individual hairs lay. I drew several studies of Lucy and photographed her before painting the final portrait in watercolour.

Except for Lucy, above, and the drawing of the young redhead further on in this post, all of these portraits were drawn directly from life.

For a moustache to look convincing make sure the underlying shape of the upper jaw is drawn correctly.

Similarly with a beard, draft in the jaw line and position the ears correctly, before overlaying the beard. With a particularly dense beard you may just have to draw the beard in relation to the mouth and ears. Getting the tones of the main masses of hair in will help to make it look convincing.

This young woman was drawn rapidly on the Jubilee Line on my way to North Greenwich. Here the head shape was drawn before adding the hair and headset.

This young girl has featured in a previous blog. I decided to just suggest her plaits rather than draw them in great detail. Again it was important to establish the overall head shape and position the ears before adding the hair. The hair was worked tonally before adding a suggestion of individual hairs in a fairly loose manner.

Note how in this portrait the facial features are framed by the hair, earrings and blouse collar. Also I have been fairly adventurous with colour, accentuating the blueness of the shadow areas. Have fun with your portraits this week! Use whatever medium you like and concentrate on hair, or a head with a covering hat, cap, headset or other!

Your drawings:

Everyone was allowed to spend up to 15 minutes on each of the sketches on the sheets below;

Very well done as there were some challenging angles and head gear!

Portrait Drawing Week 5: Mouth and Chin

July 13, 2023

This week we’ll look at the mouth and chin. The first thing to note is that the upper jaw is fixed so when the mouth is closed it is the muscles alone that enable us to smile and also to appear relaxed or concentrating. Fred in the drawing above looks as though his interest has been caught by something, he’s concentrating rather than smiling or looking sad. Notice the curve where the lips meet and the shadows below the lower lip and on the chin. This curve between the lips appears very different on the smiling lady below, as the muscles of her face pull the corners of her mouth up.

To understand what happens when we let out a yell or sing have a look at the link below where you will find an excellent drawing of the skull with jaw closed and with it dropped, and also shows the appearance of the face in these two positions.

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/448248969177542053/

Pencil by Jo

See how when the jaw drops it hinges

backwards and down toward the neck.

Below is a link to another rather more fun image showing the hinging of the jaw and various facial expressions.

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/663155113905951759/

In the pastel portrait of Beth below, her mouth is slightly open. Do resist the temptation to try to draw every tooth you can see, very often just a suggestion of teeth and of the dark areas at the sides of the mouth is much more effective than the hard look of teeth drawn in full detail. This looks especially bad if the rest of the face is treated in a softly drawn manner to convey the smooth softness of a child’s face.

So this week I would like you to make at least one study of a closed mouth and one of an open mouth.Then produce a portrait painting or a three crayon study where the mouth is a little open or wide open. You may choose to work in any medium but do pay particular attention to the teeth and go very gently, especially if you are drawing a young person.

There are instances of course, where you may want to depict a real grimace in which case you can afford to be as bold as you like!

Your Paintings/Drawings:

Portrait Drawing Week 3: Ears

June 28, 2023

Three crayon technique by Jo

Note how far back the ear is and its

relation to the line of the jaw.

Curiously our ears are not as symmetrical as all that. The ears below are from the same person. There is a general pattern but they are different. If you have a friend who will sit for you or will allow you to photograph such a delicate part of their anatomy that would be great. Not only will you spot the differences but you will get used to drawing ears of both sides of the head.

Many people find it easier to draw faces in profile facing one way than facing in the opposite direction. It’s the same with ears!

Also because we don’t peer directly at our ears in the mirror we are not nearly as familiar with the strange contours we will discover this week!

This week the challenge is to draw a pair of ears and then to draw a portrait head in profile where the ear is totally exposed so earrings are in, but covering locks are not. If you have time do some quick sketches where the ear is only glimpsed or draw what you can see of them when the head is straight toward you or in three quarter view.

When drawing the ear you may like to think of it as two curves traveling in opposite directions.

Pencil and ball point pen by Jo

Start by drawing the main outer curved shape and a straight line to indicate where the ear meets the skull. You may find the arrows help you sort out the main structures.

I tend to draw the outer round shape lightly and then indicate the straighter line where the ear joins the head. The ear is usually at a slight angle and the lower part of the ear attaches the head just above the hinge of the lower jaw. You can feel this by placing your fingers just below the ear and lowering your jaw.

There are some ear references in the “Portrait Techniques” section of my “Portraits” Pinterest board at

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/portraits/portrait-techniques/

Do look at some of the other portrait sections and note how artists have depicted ears when the head is in different positions.

Your Drawings:

Portrait Drawing Week 1: Three Crayons

June 14, 2023

Starting by drawing a portrait head or head and shoulders, over the next few weeks we’ll go on to look at different parts of the face and depicting hair, in more detail. Firstly, do remind yourself of the general proportions of the head and placement of the features. This week we’ll use the head to explore the three-crayon technique. Historically this has been used for preparatory drawings for oil portraits and also for finished works in their own right. Some examples can be found on the following Pinterest board, link below:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/coloured-grounds-drawing/three-crayon-technique/

Here you will find works by Antoine Watteau, Peter Paul Rubens, Jacob Jordaens and others you may not be so familiar with like Frederico Barocci and Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Much later artists working in this medium are Elizabeth Sonrel (1874 to 1953) and the portrait drawings of the contemporary artist Weillie Wu especially his portraits of Tibetan women and girls.

Also well worth a look is the article below about Holbein’s drawings, link below. Holbein often combined different drawing media within the same work, ink, charcoal, red chalk, etc.

For these studies you will need just three “crayons” in black, terracotta or sanguine, and white. The “crayons” may be conté crayon, hard pastel, pastel pencil or pastel. The black may be charcoal.

You will also need a coloured ground with a tooth (pastel paper or board, or a board painted with a tinted gesso). Traditionally this has usually been a warm grey or sometimes a pale green. You can make surprisingly realistic skin tones using these three colours on a warm grey. The black serves as the deepest tone but can also look quite blue when mixed with white and contrasts well with the redder chalk/pastel.

You may start with the red first or the black and hold back with the white till you are ready to add some pale areas. However there are no rules. I would advise making your initial marks with a light touch till you are happy with the main shapes. Then add stronger tones and lines.

Practical:

1. To get an idea of how the materials work together make some swatches of the colours alone and mixing by layering, hatching or blending. Each method will give a slightly different result. An important thing to notice is that the reddish chalk and white give very warm tints and the black with white gives very cool almost blue tints, so together with using the paper as a colour you have a limited but useful palette.

2. Then try drawing an oval and use the chalks to make it look as three dimensional as an egg. You could do worse than choose an egg as your first model as you can draw in the shadow as well.

3. Draw an imagined head using the three chalks. Start with either the sanguine or black; I have a preference for using the red first and limiting the amount of black. Look at the Pinterest board see how some artists work by blending the materials and others by making distinct marks with each colour and use line, hatching and overlaying. Also note how the paper is used as a tone/colour.

by Jo

This doodled head could have been developed further. The eyes could have been marginally lower unless this character’s hair was flat against her skull!

This is also a good exercise to recall the basic proportions of the head.

4. Choose a reference, perhaps a young woman and make your own three crayon study. Note that in making these drawings you will be leaving some of the paper untouched. If you find it a bit difficult, try just making a black and white, or sanguine and white study this week, and using all three crayons together the following week.

Your Drawings:

Magic of Black Week 6; Imagine and Experiment

March 29, 2023

White Posca pen and interference watercolour over a very light application of white pastel pencil

by Jo

This last challenge in the series is to use your imagination to make a story drawing and/or to experiment further with materials, perhaps using them together as in the image above.

Before this series of challenges using black paper I had hardly used interference watercolours but had used some metallics. As you can see in the sampler above they can almost appear like stain glass windows when separated by small areas of black. You may like to design your own window or paint a bird with iridescent wings.

To draw the jellyfish the upper part was drawn first and the bright base where the tentacles attach. The tentacles were then drawn with a very relaxed arm to produce a smooth and fluid line. It is best to practice this first. To prime a Posca pen the first time it is used, or during the drawing process if it does not flow freely; just shake the pen to mix the paint then press the nib down gently on a spare piece of paper. The nib will retract into the barrel. Release the pressure. If necessary repeat till ink seeps into the nib and the ink flows freely again. Always shake the pen first before using.

In the sea anemone drawing look at how opaque the paint pens are and how when dry layers of different colours can be built up. This is a rather cartoon like/decorative piece but it helped me find out how the different colours could work together. These pens are excellent for making areas of flat colour as well as for line and small bright marks like dots.

The dandelion head is made with soft coloured pencils and is an easy exercise to try which I cannot take credit for. Choose a fairly smooth black paper to work on. Simply draw the stalk with a white, a pale yellow green and a brown pencil. Lightly mark out a circle with its centre where the stalk ends. Lightly draw a yellow green area at the centre before drawing lines mostly in white radiating outwards. Start each stroke at the centre easing of the pressure toward the edge of the seed head. These lines should vary in length some ending only a short distance from the centre and others extending to the edge. Then the little white “stars” can be added with fast short strokes. Adjust the colour with a little yellow green or brown in places and there is your dandelion clock!

For the sea dragon which is related to the seahorse, a white pastel pencil was used to draw a feint outline which was drawn into with a pale cream pastel before picking the features out with an iridescent soft pastel.

Oil pastel, iridescent and metallic oil pastel over a little soft pastel and a little line work in white pen

by Jo

In the image above some areas were worked with thinly rubbed in soft pastel. A little line work in white ink was then applied before going in with oil pastel. Again the iridescent oil pastel was used as the final sparkle.

Hope you have enjoyed the last six weeks challenges and that working on black paper has been a fun and exciting way to experiment with different media.

Your Paintings;

Magic of Black Week 5: Paint a Still Life with Flowers or a Natural Form

March 22, 2023

This week’s challenge is to paint a still life with flowers or a natural form. There is no set medium and pastel, acrylic or gouache would all work well. The support does have to be black, either paper or a board primed with black gesso. The example above is gouache on a smooth black paper.

Unlike working with negative shapes, this time it may be that the object or still life group has a mainly black background. It may be useful to paint a simple object that you wish to include in the final painting to work out how your chosen medium works on your choice of support. It is an opportunity to use very opaque colour, and also thin veils of colour. My demonstration includes some Honesty seed heads, which being translucent make an ideal subject to illustrate this.

The following images may help you to get started. Choose as simple or complicated a set up as you are comfortable with. As previously, a white or pale grey well sharpened pastel pencil was used to very lightly draw in the main lines of the composition before going in with paint.

Looking forward to some really colourful work!

Your paintings:

Magic of Black Week 4: Notan

March 15, 2023

by Jo

If the Notan had been produced by the artist very careful consideration would have been made in deciding which mid tone areas to allocate to either the white or black areas of the Notan. The arbitrary limit set by the program was highly successful in this case in preserving the character and information in the painting.

This is not always the case in digitally produced Notans,

Thinking in black and white (and possibly grey)

Notan is the balance of dark and light in a composition. This Japanese word word derives from the Chinese, Nóng Dàn, which refers to Nóng meaning strong or concentrated (dark ink) and Dàn meaning weak (watery ink). We will make Notan studies using two, and three tonal values and discuss how these relate to painting in colour and printmaking. We will also see that the pattern of shapes in a successful Notan study can be more than a strict reflection of tonal values.

One of the best ways to develop a strong composition is to build a strong pattern of lights and darks. A Notan study will help to identify these patterns before embarking on the final work. Whether working on black or white paper It is helpful to draw the main shapes swiftly but accurately to avoid getting bogged down in details. This could be done with a white pastel pencil if working on black paper. Then all the pale area areas can be filled with white ink or paint. It is relatively easy to identify the darkest areas but when it comes to the mid tones you should try to assign these areas to light(white) or dark(black) values which best convey the sense of what is happening in the picture. This applies whether you are working from life or from a photograph. Where only two tones, black and white are used the Notan study is called a 2 value Notan.

Some compositions are better described by 3 value Notans where the subject is reduced to black, a mid-tone(grey) and white. It is of course very possible to include more values but for our purposes 2 and 3 should suffice.

Do read the short introduction to Notan by Mitchell Alabala which very eloquently describes how Notan is linked to shape and patterns that define the structure of a composition rather than being studies totally defined by tone ; links below

https://mitchalbala.com/the-wisdom-of-notan/

And look at the accompanying 13 minute video

https://mitchalbala.com/video-exploring-composition-though-shape

You will see how this is especially the case where different colours that are similar in tone make distinct patterns of shapes over the whole area of an abstract work.

Practical: Try making a 2 value Notan, and if you have time a three value Notan;

Choose to make these from an existing well known artwork, a simple still life set up or a photo reference. This will be easiest where there are well defined areas of light and dark as in a portrait or still life lit strongly from one side. Identifying the main shapes and eliminating unnecessary detail is the key to a successful Notan as is including necessary detail and careful assignment of the mid tones in a two value Notan. In the Notan derived digitally from a photo of a painting at the beginning of this post much of the detail could have been eliminated leaving a stronger pattern of larger shapes. Necessary detail may be a tiny slither of light or glint that makes sense of the overall image.

Making a 2 Value Notan

1.Find a reference ( photo or art work) or work from a simple still life set up. If working from a reference try to find one with strong contrasts and relatively simple shapes. Mark out a rectangle of the correct proportions on your paper.

2.Identify all the main shapes by tone. Decide which mid tones will be assigned to the black of the paper and which will be painted white. On black paper this could be done by working with a white pastel pencil to establish the proportions of the main light and dark areas.

3.Block in the light areas with white paint or ink.

4. If you have time make a second study from the same reference and assign the mid tones assigned rather differently. Think about which Notan is most informative.

Making a 3 Value Notan

1.Find a reference and then mark out a rectangle of the correct proportions as before.

2.Identify dark, mid tone and white areas and mark them with a white pastel pencil or white coloured pencil.

3.Then paint in the mid tone and white areas. Sometimes it will be easier to paint all areas that are not to be left black in white first, and then to add the mid tone over the top. In other cases it may be easier to paint everything except the darkest with a mid tone grey first, before adding the palest parts in white over the top.

4.Please send an image of your reference as well as the Notan studies. Reference material will not be published on the blog but would be helpful for the review.

produced digitally

by Jo

In this instance although the 3 value Notan describes the image a little better, the subject can be very well understood from the two value Notan.

Below are a few additional notes:

Digital Notans

There are several computer programs which will provide you with 2, 3 and more value Notans. These do not always convey the spirit and energy of a reference in the way that your personal Notan study will. This is because an arbitrary and fixed threshold of what will be designated as dark or light may be different to the best way to communicate your subject. Some areas of the composition may require a different threshold to communicate that. That said, if you have problems in beginning your studies, seeing the results of a digital process can be helpful. One of the other problems is that a digital process will not simplify the shapes for you.

Notans and Printmaking

After making a few studies you will soon see the practical relevance of making Notan studies both to analyse the patterns of shape that inform a composition for painting and also for print making, especially for relief printing where you will need to clearly define the shapes that will be inked or cut away so they are not inked.

Decorative Notans

by Jo

Here fish and sea weeds were cut out of a square of black paper. The paper and and the positive shapes cut from it were pasted on to a white piece of card.

Interesting designs can be made by playing with positive and negative shapes as in the sea and fish decorative Notan above. This is a really fun way to play around with shape and pattern.

Your Notan Studies:

Some of the smaller shapes detract from the fact that Liz has observed the larger shapes very well. Because the paint did not cover well in places Liz’s Notan was made to look flatter digitally.

Magic of Black Week 3: Night Scene

March 8, 2023

Pastel on Black paper by Jo

Note how the tree trunks are “not drawn or painted”.

All the drawing is in the spaces between.

Working on black paper lends itself well to drawing and painting night scenes just because they are DARK. Lights from street lamps, moon and stars can be depicted simply and dramatically.

Watercolour by Jo (unfinished)

The main lines were lightly marked with pastel pencil. Masking fluid was applied to all areas that were to remain black. The paper was dampened then washed with layers of blue and green interference watercolours using a large mop brush. These washes were modified with smaller brushes. The painting was allowed to dry thoroughly before removing the masking fluid.

Pastel and pastel pencil, or gouache or acrylic would work well. Paint pens could be useful for the odd bright pop of colour. Happy for you to experiment and mix the media. When working with pastel white gouache can be used to accentuate highlights. Pastel can also be applied as over gouache or paint pens where a softer effect is needed. Most watercolours are too transparent for effective work on black paper but mixing with a little permanent white increases opacity and the effect is similar to working in gouache.

Work from a reference or your imagination. In either case think very carefully about which areas you wish to leave as untouched paper or with a thin veil of colour and which areas need to stand out brightly. Whether working in pastel or gouache it can be useful to mark out the major areas of the composition very lightly in pale pastel pencil just to give a road map. Deal with the mid tone areas and then add the brightest areas of light as the finishing touches.

Tiny pastel by Jo 4 x 5 inches

Here the tower is left as mainly untouched paper.

Pastel and Pastel Pencil by Jo about 4 x 5 inches

Note the arrangement of light and dark areas, use of line and use of broken colour. In this drawing the trees trunks and branches were drawn first before laying in the misty areas. The leaves were then added as bright dots and dashes of white and near white broken colour.

Pastel by Jo

This red cloud is an imagined galaxy full of white stars. Each star is made to look luminous by making its immediate surround dark giving a huge contrast with the star embedded in the light to mid tone dust cloud.

Pastel and Pastel Pencil by Jo

Here the moon is made to look luminous in the same way as in the previous image except the full moon is surrounded by a small ring of untouched paper then a halo of mid tone. Note the reflected light on the cloud, the reflection in the water and the moonbeams lighting up the landscape.

Photo by Jo

Imagine how it would be to use this photo as a reference and how all black areas could be represented as untouched black paper, while making the lights brilliant.

Also identify the main areas of mid-tone.

Photo by Jo

This could also be painted on black paper reserving the black of the paper for the palm trees and telegraph pole. How could you deal with the wires? Night scenes like this and the photo above could be painted in pastel or gouache.

This week is really an introduction to painting the negative spaces between the trees and other objects that block the light. it’s also a great opportunity to make lights that appear truly luminous in your paintings. Happy for you to work from the photos above, from your own reference or from your imagination using any medium.

Practical

1.Choose a night scene photo reference or work from imagination.

2.Work our your composition on a small piece of black paper and do some experiments to find which medium or media will suit your subject best. Mixing the media may produce an exciting result.

3.Map out the composition very lightly with a pastel pencil on the paper selected for the final work and then create a work where some of the paper is left untouched or is visible beneath translucent layers of colour.

Your Paintings:

Magic of Black: Week 2 Dots Lines and Shapes

March 2, 2023

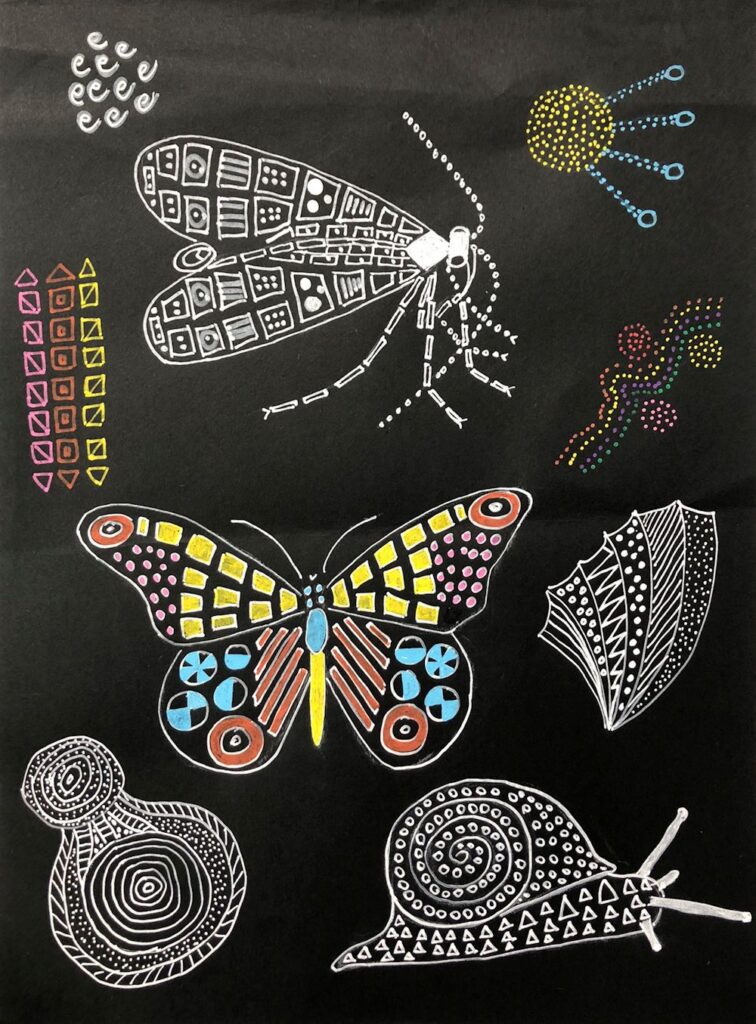

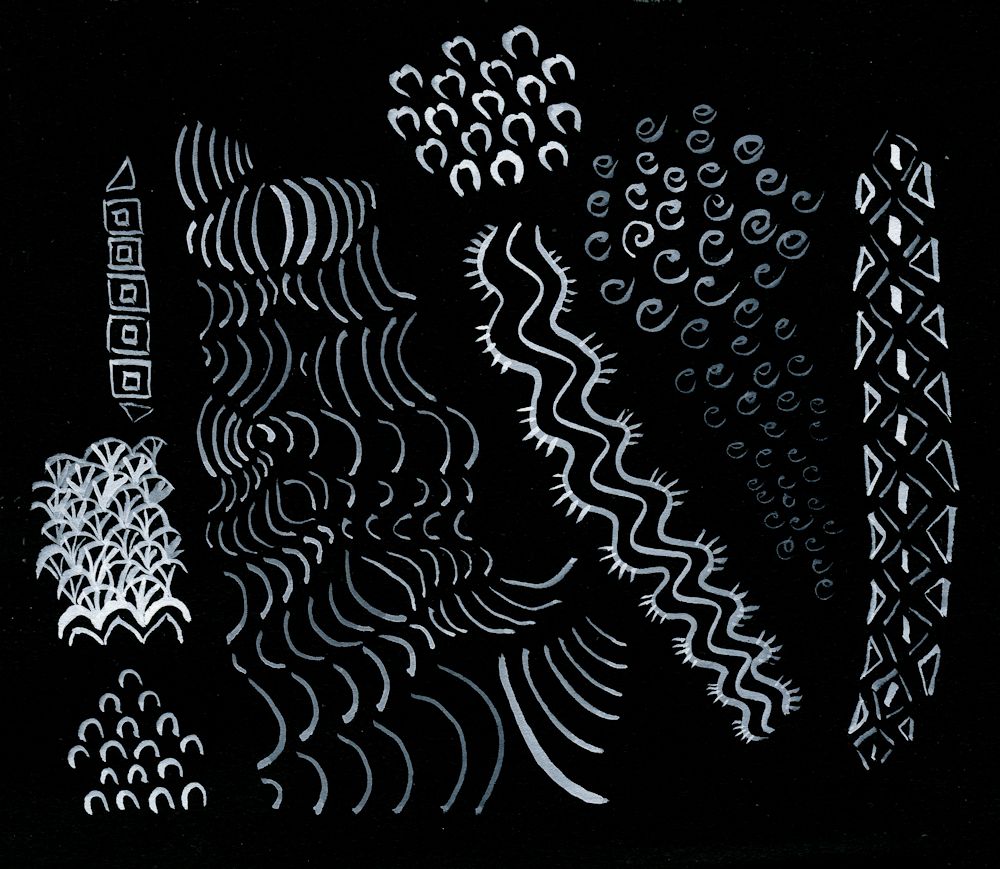

This week we’ll explore making patterns of dots, lines and shapes to create texture or to make illustrative or imaginative drawings. If you are working with very small marks don’t attempt a large piece. The moth drawing above was only about five inches by 3 1/2 inches. If you decide on exploring shapes this can be as large or small as you like but for a large piece use large brushes or chunky materials to suit the scale.

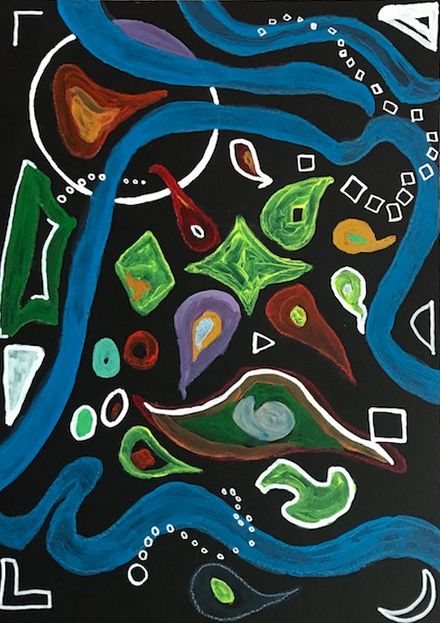

Happy for you to experiment with seeing a scene in plan view. As in the drawing below.

Gouache by Jo

Note how the dots have been used to make patterns of eddies in the river. The scene is as if in plan view so the green circles are trees. The palest dots have been used to mark out the main areas.

The composition relies on the shapes; the arrangement of the large areas and the arrangement of the colours and tones of the dots. There is no attempt to create an illusion of three dimensions but there is a sense of movement.

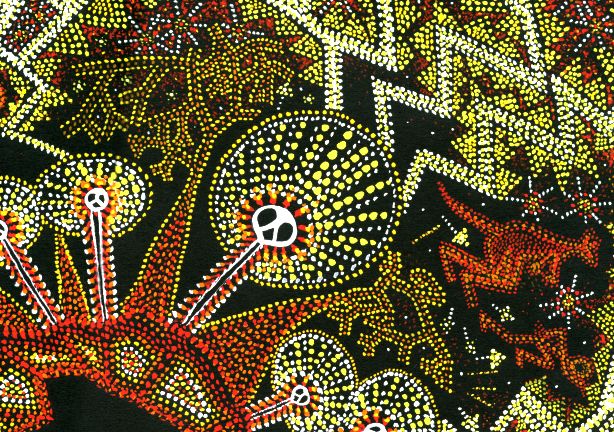

Dots

Shapes, dots and lines have been used in very ancient rock art and also the more recent and intriguing dot paintings of aboriginal artists in Australia. I took inspiration from both rock art and dot paintings for the “Ring of Fire” drawing below. The dots are used in two main ways; firstly to fill shapes and secondly to form lines to mark out the main areas/motifs of the composition. They can also be arranged in lines making decorative patterns as in the haloes of the lightning spirits below which are filled with radiating lines of dots. Unlike the Meander drawing where the dots are placed close to each other over the whole work, in the drawing below the black paper between the dot motifs plays a much more significant role in the composition.

Gouache by Jo

This dot painting combines ancient cave painting motifs of lightning spirits with a dot technique. Gouache was used and applied with a small round brush held vertically to make each dot.

Note how the colours are used to produce pale and mid tones on the black paper.

Patterns of lines

Similarly lines can be used to form patterns within a composition or as the basis for its structure separating one area from another. By altering the density of marks across a shape both lines and dots can also describe form as we saw from the scribbling marks in the previous post.

These can be free and organic or more geometric: experiment!

Another consideration is perspective and acuity. If you reduce the size of marks so that those at the bottom of the paper are large and gradually become smaller the further up the paper they occur they usually read as being more distant rather than smaller in size. Imagine a long shingle beach. The stones closest to you are seen as distinct individuals; further away they form an irregular pattern, further still they are seen as a texture but can no longer be sees as distinct entities; yet further away they will just be a colour in the distance.

Decide whether you would like the marks to speak for themselves or whether you would like to add thin veils of watercolour or pastel as in the image below.

Mixed media on black paper by Jo

White marks were made freely with a white paint pen then dilute washes of permanent white gouache added and also some black India Ink marks for the trees. Finally, coloured washes of green and yellow ochre watercolour were applied.

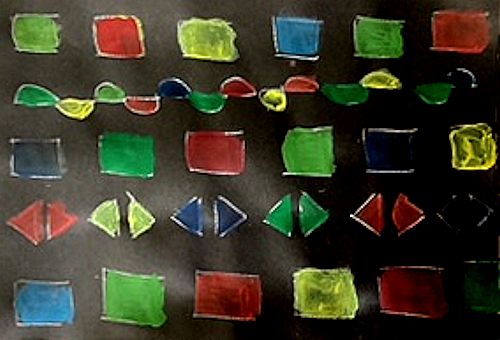

Shapes

Try working intuitively with shapes on black paper. You may work in white or colour. If you don’t have any gouache colours, just add some permanent white gouache to your watercolour mix to make it more opaque. If you already have some gouache paints you won’t have to add white unless you need a paler tint.

This tiny sampler 2 1/2 x 2 1/2 inches was painted with some Derwent Graphitint pans which proved to be very opaque.

For this week’s project you may like to work intuitively or be inspired by natural forms. You may also like to look at the following Pinterest Boards on pattern and rock art.

Rock Art

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/magic-of-black/rock-art/

Abstract Pattern

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/magic-of-black/abstract-pattern/

Patterns of Nature

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/magic-of-black/patterns-of-nature/

Materials you will need

Black paper; white gouache and brushes or white ink or paint pen, watercolour or gouache colours;

You could alternatively work in pastel pencils or pastel or mix the media.

Have some India Ink ready as it can be used to reinstate black as in the waterfall drawing.

1.Experiment with making patterns of dots, lines and shapes. Aim to work a small sample of each and using all three together.

Then do either 2 or 3

2.Make an abstract or near abstract composition of lines and/or dots and/or shapes. Some lines and dots may overlay areas of colour. Try to make the black support an important element in the work. The work may be very free and organic or more geometric. The rock art and abstract Pinterest boards may give some useful inspiration.

3.Make a finished drawing/painting inspired by natural forms or landscape. Think about what drawing marks will suit your subject and composition best. Use at least one of the techniques described. The marks and shapes may “speak for themselves” or you may like to add veils of colour with dilute watercolour or pastel to soften them.

Your paintings:

Magic of Black Week 1: Drawing and Mark Making

February 21, 2023

White paint marker and watercolour on black paper

by Jo

Note the use of scribbling technique and restrained addition of watercolour washes. To see more of the scribble detail right click the image to open in a new tab,

Over the next six weeks we’ll explore using wet and dry media on black paper. We’ll look at the drama of working in near monochrome as in the castle drawing above and more decorative and fun ways of working. Facing a blank black sheet instead of a white one requires a radical rethink as to the effect marks on the paper will make. Somehow it can be less daunting than the scary white sheet!

For most sessions black paper will be used but you may like to consider using an off cut of black mount board which makes a great support for detailed work in gouache, or perhaps canvas or board coated with black acrylic gesso.

Topics will include; mark making (especially the first two weeks), drawing and painting with wet and dry media including soft pastel and/or watercolour; negative painting; making a decorative notan with positive and negative shapes; and using pearlescent and/or metallic paints or inks if you have any. For those who enjoy working in fine detail we’ll also discover the effectiveness of starting with a black support.

For this week’s project you will need either a white paint marker (Posca or similar) or a pen and white acrylic ink. Alternatively a white gel pen, or white gouache or thinned white acrylic and a fine brush. You will also need some watercolour, a tube of permanent white gouache and perhaps a couple of soft pastels or pastel pencils. best to read, find the materials and experiment.

1.Open and closed shapes;

Lines can be used to show the boundaries of shapes. Where a line completely encloses a shape the shape is often referred to as a closed shape as in the letter “O”. Where the line fails to completely enclose a shape the “shape” is often describes as an “open shape.” In reality an open shape is just a line as when you draw the letter “U” or “V”, but all these lines can be harnessed to create pattern within larger shapes as in the surface of the fish drawing below.

Draw or paint some open and closed shapes on an A4 sheet. Fill some of these with more open and closed shapes. Allow to dry then try painting thin veils of watercolour to fill some of the shapes. You could also try surrounding some shapes with a different colour of watercolour or pastel. Experiment with straight sided and curved shapes. Try to leave some of the surface unpainted.

A shape that is completely enclosed by a line, like a circle or square is considered to be a closed shape. Shapes like the letter “U” are not completely closed and can be considered as open shapes. Open shapes are best considered as lines which may be straight, irregular, zigzag, wavy etc.. Here the pattern on the fish is composed of mostly closed shapes and dots. The small shapes that are not completely closed are open shapes.

Note how effective the use of pastel surrounding the large fish shape is.

2.Draw a closed shape (e.g. pear or fish shape or an abstract shape like a circle,)

Scribble with white lines so that the shape is densely marked on one side and the marks gradually become less dense toward the other side lending a form to the shape (this might be top to bottom if you choose a fish shape! When dry overlay a veil of watercolour or pastel over all or part of the shape. Try something similar if you have time using hatching and cross hatching instead to show the form. In practice sometimes the rather organic texture of the scribble would be preferred and at other times hatching techniques are best. I’m a compulsive scribbler and when using pencil usually prefer continuous tone rather than hatching BUT we all work differently and either way the marks made by any individual are unique and contribute toward their style of drawing.

3.Make a more considered drawing, still life, land form or natural form like a pepper or fish using similar techniques.

The scribbling technique can be very useful for rocky landscapes or to show the form of a fruit like an apple. Open and closed shapes can be useful for the patterns on a variety of natural forms and vegetation. If using very wet watercolour, black watercolour paper would be best for the more considered drawing but any black paper or a reasonable weight would be fine for mark making and pastel or small areas of watercolour.

Your Drawings:

Birds in the Garden: Week 4

November 23, 2022

Sketch of the blue tits above from this week’s session is almost finished; its back needs a bit more attention. I’ve included it to show how the vegetation of twigs and bushes can be shown with little strokes and leaves almost printed with the brush.

This last week you are invited to paint a colourful finch or the grey and brown house sparrow.

After choosing your bird try out some sketches of its body shape in different attitudes before planning the final composition. You may choose to make a detailed study of one bird or of one or more birds showing the sort of habitat they dwell in and what they are perching on etc. Research in bird books for details of markings etc. and you may find a clarity not always evident in photographic reference. Try not to copy either sort of reference slavishly but let both kinds of reference inform your painting. The best way is to observe from life whenever you can and with a little practice it is surprising how much you can draw from a moving subject. Birds often repeat movements and you can start a variety of little drawings on a page that are initially no more than a few marks, which you can build on till they become bird shapes with a lot of vitality.

Do also look at the following Pinterest boards;

Finches at:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/finches/

Sparrows at:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/sparrow-photos/

We’ll talk about the colour mixes for the Finches and Sparrows at the session and fix a short review session for the following week.

Your paintings:

Birds in the Garden: Week 3

November 16, 2022

First a recap on this week’s painting session

Two ways of delineating feathers on a dark bird:

The blackbird above was painted in watercolour, painting the flight feathers paler than the rest of the wing. With a fine brush the individual feather edges were painted in. When dry the wing was too light so a further wash of a dark grey mix was added and the feathers reinstated just a little.

Another way to paint the details of feathers on a dark bird is to paint everything in the dark tone that it appears and to add any necessary detail with mixes of white gouache and watercolour:

This week we’ll be looking at the colourful Blue Tits and the slightly heavier looking Great Tit with its black cap. Do look at any tit family references you have and the Pinterest board at

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/tits-photos/

and come to grips with making a few rapid sketches either before or at the beginning of the session. As before take in what the main body and head shapes look like when the bird is perching, on the ground or turning its head. Also look at the legs and claws.

We can use these sketches to apply trial mixes of the colours needed for a more considered painting. Blue tits are often seen, two or three at a time so you may like to consider making a composition with more than one bird. If so, do plan this in your sketchbook first before making the drawing on watercolour paper. Perhaps also start to think about the background for the birds and make a tonal sketch.

The drawing on watercolour paper or in preparation for working in acrylic, should be detailed enough to show the main feathers of the wings and indicate the position of the markings, as well as placing the beak, eye, legs and claws. Draw just enough of the background to aid the composition and plan to create most of the background with paint always aiming to make the birds the focal point.

Make sure the pencil marks are not too dark and lighten them if they are. If working in watercolour, reinforce the main lines with a pale blue/grey painted line using a small brush and then put a light blue grey wash over all the slightly shadowed areas of the birds. (If working in acrylic just establish the main shapes of colour and tone and gradually build into this with the smaller shapes and marks.)

Then mix up your washes and try them on your rapid sketches. For the blue tits you will need a blue, a yellow, a green for the back and various grey/black mixes which can be added last. You will also have to be careful if working in watercolour to leave the paper untouched by paint for the white areas.

Then start to paint your bird; probably eye and beak first, then suggest the legs before painting the paler areas of colour followed by any blue and green and finally the darker areas remembering to reserve the white areas.

Try to add colour as washes where the feathers are tiny as on the breast, head and back. It is often better to suggest the texture a little in places later if neccessary, rather than paint a lot of feather like strokes in the beginning. The wing feathers need a different consideration as when the wing is folded against the body some feather edges appear as stripes of light and dark. The light is very often not white so a wash of the right pale colour needs to be painted first and allowed to dry before painting stripes of the darker colour over the top. Your initial drawing should indicate where this needs to be done.

There are no rules as to the stage when you start painting the background. If the birds are in trees or bushes it will be integral to the drawing and if on the ground, you will have to indicate whether it is grass or path etc. or your birds may be seen partly with a backdrop of trees and partly of sky. We will discuss backgrounds during the session, especially about whether these should be just suggested or more definite and what will suit your purpose best.

Your paintings:

Birds in the Garden: Week2

November 10, 2022

This week we will be looking at Blackbirds and the Song Thrush, just as familiar to us as the Robin and Wren. Biologically they belong to the same family and both have a similar and much longer body shape than the very compact wren and robin. I have drawn blackbirds from life but the ones above and below were hasty sketches in pencil from photos, livened up with some watercolour washes. Apart from drawing a more elongated form the main challenge in painting the blackbird is that it is completely black! This means more attention to tones and how the light is falling on the bird. Often they can look like a silhouette against a pale background.

In watercolour the paler areas will be more lightly washed. With acrylic or oil you will be mixing greys and should take care that they don’t look too chalky. You may like to experiment making black with mixes of blue and brown. I did that with the first image and then went in with some Payne’s Grey which resulted in a warmer feel. As these were on cartridge paper and some of the washes were quite wet they were not as controlable as on watercolour paper, but as in the rapid sketches we made last week the aim was to capture the body shape and some characteristic poses. Studies like these are perfectly adequate as a reference when for instance the artist wishes to include birds in a landscape painting or birds feasting on the last of the berries or apples before winter sets in. Even in these sketches I did include the yellow ring round the blackbird’s eye.

For a more detailed study of a blackbird where the artist wishes to illustrate the wing feathers and the shiny black eye surrounded by a narrow yellow rim with more definition, some different strategies are needed. There is no one right way but you may like to try the following;

1.Watercolour: This will be demonstrated at the next session by painting a wing and its feathers, using watercolour and either cold or hot pressed paper. The whole wing will be washed in with tones that reflect the overall tonal values observed. The colour mix can be made from blue plus brown and/or Payne’s Grey. For a female or juvenile bird you will need brown mixes, perhaps with a little blue or even a small amount of red in the mix.

When this is completely dry use a small(tiny) brush to apply an appropriate paler grey mix made with opaque white gouache to the edges of the feathers where they catch the light. This requires time and patience and there will be places where the feathers are better just suggested and others where more definite marks will be needed. Very often once dry a little blending may be needed to soften some lines. Another way would be to lift out the lines with a moist brush.

For paler and more colourful birds try applying a pale tonal wash over the shadow areas(usually a blueish grey mix). Then instead of adding the paler stripes you can paint the feathers one by one leaving dry paler or untouched paper below. Will try to demonstrate this for the thrush or wren drawn last week. This method also works well for birds like tits and finches where it is only needed for limited areas. For a detailed account of this look at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YCuDNFcFz8

Watercolour Birds Part 1: U-tube video by John Muir Laws; a bit long but excellent

2.Acrylic: You will need similar colours to paint the main areas of the wing first except that you will be varying the tone by adding white. Also look closely at the wing feathers, sometimes the wing coverts are a slightly different tone or hue to the flight feathers. The wing of a female bird is browner and may show more variation n colour. Again think about where it is essential to show feather edges and where a suggested texture is desirable, then mix up a suitable colour and apply lines for the individual feathers with a small brush.

During the session we will make rapid sketches of the blackbird and the song thrush. Strategies for painting feathers will be discussed and demonstrated and we’ll talk about the markings on the front of the thrush. Note that the thrush is a slightly smaller and slimmer bird and although it doesn’t have the yellow rim the blackbird has around around its eye, the thrush eyes appear a little larger and have a surround that is very pale.

Blackbird pictures can be found at

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/blackbird-photos/

Thrush pictures can be found at

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/thrush-photos/

At any stage after the warm up sketches feel free to start your own study of a wing, or a picture that includes blackbirds or a song thrush. You may like to paint a few blackbirds at the base of a tree picking up worms or pecking at apples.

Your paintings:

Birds in the Garden: Week 1

November 2, 2022

This first week we’ll start by sketching a few bird shapes. Some like the Wren and Blue Tit are rather round and compact whereas the Song Thrush and Blackbird have a rather longer more elegant shape. I love the way a blackbird can turn its head. If you can, take time to watch the birds in your garden. With the cooler weather we often have several Blackbirds pecking away at the last of the apples on the ground. If you are quick enough you can doodle a gestural line or two in a sketchbook while you watch them. With practice you will soon be able to draw their body shapes turning and twisting among the fruit.

It’s easier of course to draw from photos, but if you work fast from birds in very different poses by direct observation or from photos you will learn how to make your drawing appear lively and not laboured. With fast sketches we can record the direction of movement rather than detail, the body shape as the bird moves, and the balance it achieves whether perching on a branch or hopping around on the ground. This is the skill required to include birds in paintings of gardens where several birds may make a huge presence but only occupy a tiny area of the composition.

At the other end of the scale, and this is where photo-reference can be invaluable, the artist may wish to make a detailed portrait of an individual bird or a field sketch noting all the characteristic markings and colour of a particular species. Some examples of these can be seen on the Pinterest Board, link below:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/small-garden-birds-representational/

In either case observing birds in your garden and how they move will feed into and inform more detailed studies. Garden birds also feature in art in a more narrative and fictional way and some of these paintings and illustrations are shown on the following Pinterest Board, link below

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/birds-with-a-strong-narrative-element/

Observation points; you may not be able to observe all of these in any one view.

First look at the following Wren and Robin boards:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/wren-photos/

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/birds-in-art-and-photos/robin-photos/

Pay attention to; overall body shape; head and beak; relation of head to body; how upright they stand; see what happens when they turn their head, sing or put their head down; wings and tail shapes and relation to the rest of the body; leg length and how they join the body; feet and their appearance when perching on a branch or on a flat surface; feathers; markings and colour.

Practical

1. Fast Sketches

This week we’ll choose to work from a couple of very small birds, the Robin and the Wren. First of all I’ll share the screen for some rapid sketches of each bird so have a sketchbook and pencil at the ready to draw several birds on the same page.

2. More detailed Studies

Before the session, find a reference to paint a more detailed study of a Robin or Wren. If you can, start two small paintings during the session and complete them afterwards sending images to me before the following week. In the first painting draw/paint exactly what you see in your reference. In the second study try painting the bird in a different position and change the background using the experience gained from the rapid sketches made earlier.

For sketches use any drawing medium with which you can work swiftly; for me at a small scale that would be rather conventionally a pencil! For more detailed studies in colour you may choose any coloured pencil including pastel pencil, which works well with coloured papers, or any painting medium. The Robin heading this post was painted in acrylic but watercolour or gouache would be a favourite for field studies.

Your Paintings:

Almost Monochrome Week 4

September 21, 2022

Every stage of a painting has its merits. Often as in the monochrome painting below, the initial rapid response to the landscape is more exciting than the finished painting.

Starting with a cool colour

The initial acrylic sketch was made with a cold blue grey made from Cadmium Red Hue and Phthalo Blue, mixed with white. The painting was completed with purplish reds made with Cadmium Red and Phthalo Blue, almost pure Phthalo Blue and white form much of the water and adding Yellow Ochre into the mix for some of the vegetation.

Stage 1: A large amount of a mix of Phthalo Blue and Cadmium Red Hue was made to make a cool blue grey and a basic monochrome sketch made in acrylic. Some further Phthalo Blue mixed with a little white was added in places. This will form a monochrome structure for a more colourful painting.

Acrylic by Jo

Completed with additions of mixes of Phthalo Blue and cadmium Red plus some Yellow Ochre

Starting with a warm colour

Burnt Umber and white was used for most of the first stages of the painting below, with added mixes of Phthalo Blue. The result was a much warmer sketch. I wanted the bridge to appear set into the landscape more and to show the green colour of the nearer hills. The bridge and tunnel are exactly the same size at each stage shown but note the illusion of the bridge looking smaller when painted closer in tone to its surroundings and the trees painted to cover more of the lower part of the bridge. In the final painting the tiny patch of pale riverbed/path/water, near the bottom left is the point of most contrast and appears much nearer to us than the bridge, reinforcing the illusion of depth in the painting.

Stage 1: monochrome painting in Burnt Umber and white to

which mixes of Phthalo Blue with Burnt Umber have been added.

Acrylic by Jo

The completed painting. Although I liked the freshness of the initial colour sketch I wanted the bridge to appear more set into the landscape and to show the greenish tinge of the rocks in that part of the Parma Apennines. The foreground hills were reworked a little and the bridge and tunnel made very slightly darker so that it receded. The foreground and middle distance trees were also worked on and at some stage the bright Sienna foliage on the nearer trees may be reinstated.

Although not as exciting as the initial sketch the finished painting does remind me of a hazy day with the last remnant of Autumn colour in the trees rather than the brightly lit bridge of the first stage. Note how using a cool or warm colour can alter the atmosphere. The cold Phthalo Blue mixed with the warmth of Burnt Umber meant I could choose between keeping the painting warm as in the initial sketch or making it far colder in appearance.

This week I would like you to complete any unfinished work and to make a tonal painting in a rather different way. The challenge is to paint a contre jour subject. This could be a landscape against a bright sky or sunset, or a simple still life in front of a bright window. The subject will not be a completely stark silhouette but may appear dark and with subdued tones against the light.

I have put a few examples of contre jour works on the following Pinterest board, which includes some delightful paintings by Anton Mauve, link below:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/jhall1282/limited-palettes/contre-jour/

Think carefully about how you would like to start the painting. If it is a sunset landscape it may be good to start by painting the sky especially in a work with trees and a low horizon. If it is a still life in front of a window you may like to paint the dark of the window frame and the objects before painting the light through the window. In either case think carefully about the pigments for the main tonal areas and whether your finished painting will have dark tones that tend toward warm browns or dark tones that tend toward cool blues and greens. Keeping to a restricted palette as we have done over the past few weeks, make a mainly tonal painting of a contre jour subject.

Your paintings: